Chennaiites feel a slight sense of relief and hope, now that the number of COVID cases reported in the city has dipped considerably. However, the city will breathe easier when the mortality rate can be controlled. As on July 27th, a total of 2,032 patients had succumbed to the disease in Chennai.

According to Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC), Chennai’s overall mortality rate is 2.12% as on July 27th, which is marginally lower than the national average of 2.25% on the same date. However, within the state, it remains the highest and has been a cause of concern for citizens and authorities alike.

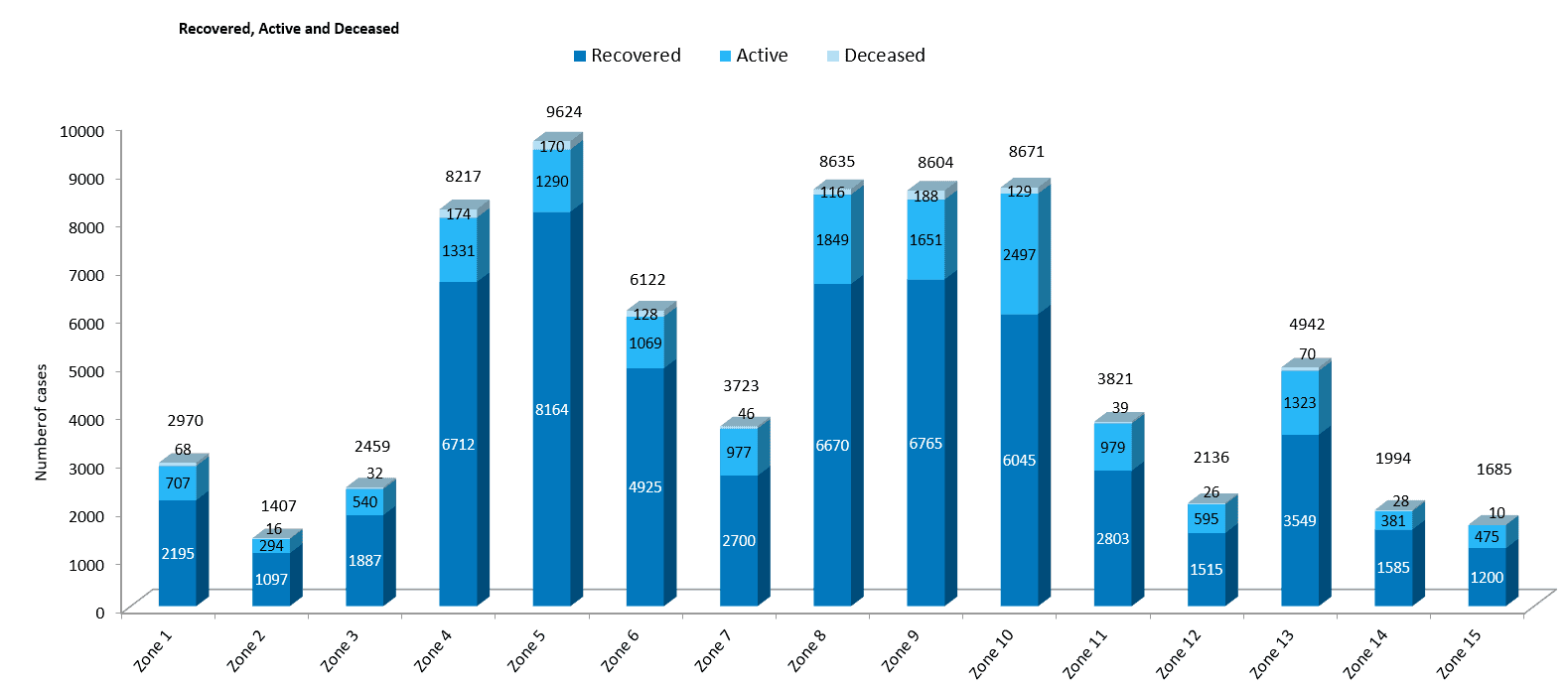

Within the city, Zone I (Thiruvottiyur) records the highest mortality rate of 2.25%, whereas Zone V (Sholinganallur) records the lowest at 0.62%. A closer, more granular look at the data pertaining to deaths in the city, throws up interesting insights.

Data between May 1 and July 13th provided by the state health department highlights several details regarding deaths resulting from the coronavirus infection. Here are some of the key findings on important indicators — from zone-wise mortality rates to the importance of timely hospitalisation and the presence of co-morbid conditions, :

Which zone has the highest mortality rate?

Data released by the GCC shows that Zone I (Thiruvottiyur) has the highest mortality rate.

With 68 deaths among the total 2,970 positive cases recorded in zone in the period till July 13th, more than two in every 100 COVID patients (2.29%) in Thiruvottiyur have succumbed to the disease.

A very close second in the list is Zone 9 (Teynampet), with a mortality rate of 2.19% and Zone 4 (Tondiarpet) with 2.11%.

But why did Zone 1 register the highest number of deaths?

An official from the civic body informed us that Zone I has 15,744 COVID patients with co-morbid conditions due to which the mortality rate is high. “To address this, we have been conducting three special camps in the zone to detect the underlying diseases in COVID patients and give special care,” a senior official stated.

The camps are happening at the Urban Primary Health Centres at Kathivakkam (Division 1), Kuppam (Division 3) and Thiruvottiyur (Division 4).

However, according to sources in the State health department, the high mortality rate is also linked with gross negligence in detecting comorbidities in COVID patients by the civic body when the pandemic broke out.

| Zone No. | Deceased | Total COVID cases | Mortality rate (Deaths/cases*100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 | 2970 | 2.29 |

| 2 | 16 | 1407 | 1.14 |

| 3 | 32 | 2459 | 1.30 |

| 4 | 174 | 8217 | 2.11 |

| 5 | 170 | 9624 | 1.76 |

| 6 | 128 | 6122 | 2.09 |

| 7 | 46 | 3723 | 1.23 |

| 8 | 116 | 8635 | 1.52 |

| 9 | 188 | 8,604 | 2.19 |

| 10 | 129 | 8,671 | 1.49 |

| 11 | 39 | 3,821 | 1.02 |

| 12 | 26 | 2136 | 1.22 |

| 13 | 70 | 4942 | 1.42 |

| 14 | 28 | 1685 | 1.40 |

| 15 | 10 | 2327 | 0.59 |

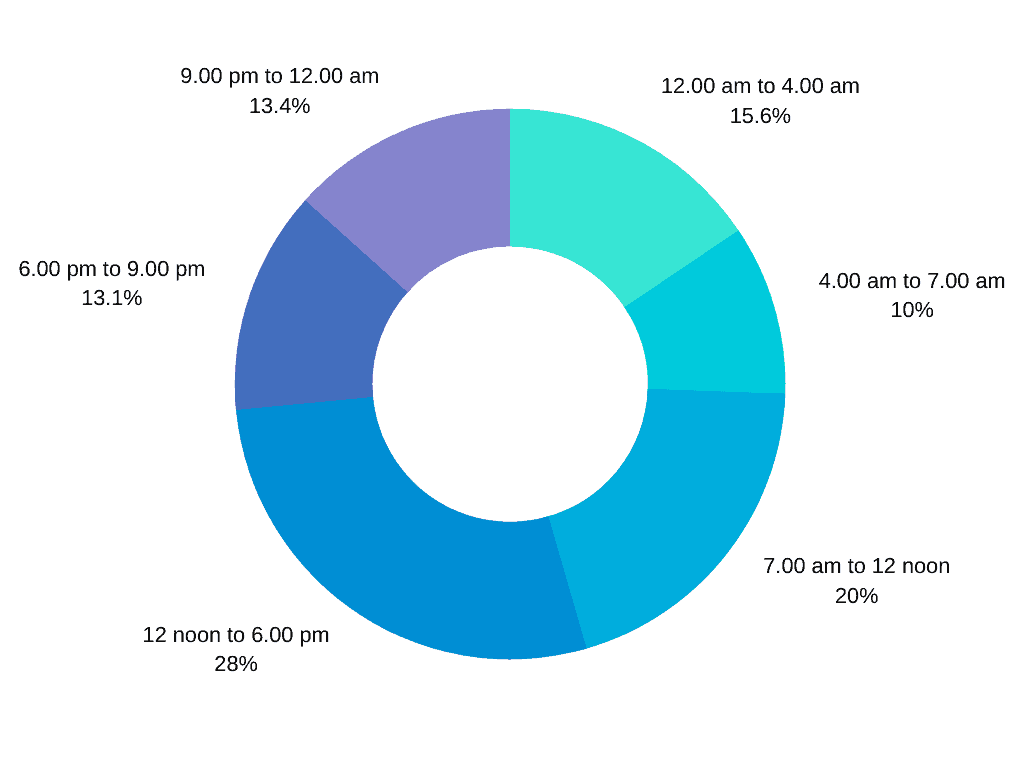

Deaths during wee hours

Marking a strong pattern, 368 deaths (till July 13th) occurred in the wee hours. 198 patients succumbed to the virus between 12 am and 4 am and 170 patients between 9 pm and 12 am.

Dr Amalorpavanathan J, Retired Director of Vascular Surgery, Madras Medical College, has an important observation. He notes that the incidence of casualties is particularly high in the early mornings, when the hospital staff are also exhausted and drained, mentally and physically.

“Most early morning and late-night deaths are caused due to silent hypoxia where the oxygen level dips in a human body. In this case, the patient does not exhibit any symptoms in the initial stages of the dip, unless s/he is constantly monitored,” says Dr G R Ravindranath, general secretary, Doctors’ Association for Social Equality (DASE).

This strongly underlines the need for more healthcare workers who can be deployed on a shift basis in Chennai public hospitals, so that a huge number of patients can be monitored consistently, even during the wee hours.

Admissions in the eleventh hour

A close analysis of the data also shows that 34 COVID patients who succumbed at the Government Royapettah Hospital (GRH) died within a very short time from when they were admitted.

Of the 34 patients, 30 died within 24 hours, two died within 48 hours and one person was alive for a little less than 72 hours. Data for one patient is unavailable.

Similarly, at the Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, which recorded the highest number of deaths (RGGGH), 36 patients died on the same day that they were admitted to the hospital. 56 succumbed after a day of admission and 76 within two days. In Stanley Hospital, 13 patients died on the same day, 38 after a day and 25 after two days.

The data points emphasise the need for closer monitoring of patients in home isolation and the need for faster hospitalisation when a patient grows critical. 21.57% of the deceased population died within a short span of time in hospitals in the city.

Deaths with comorbid conditions

Among the total deceased population, 79% (1,011) patients had comorbid conditions; 56.27% (722) had diabetes and 44.11% (614) had hypertension.

Diabetes is a metabolic disease that goes on to affect other organs and lead to other conditions such as diabetes retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy and diabetic foot among others.

“People with diabetes are immunosuppressed, which facilitates the entry of the virus into the human body. Viruses thrive in such habitats. When COVID infects a diabetic patient, it becomes difficult to control the glucose levels that increases the probability of the patient succumbing to the disease,” explains Dr Syed Hafeezullah, Internal Medicine expert, who is on COVID duty at a private hospital.

Institutional negligence

Besides the medical reasons behind deaths as revealed by the data, anecdotal evidence also suggests that institutional callousness and negligence has been a key factor in some deaths. Interactions with family members of the deceased reveal that in many cases, the staff at the hospital did not consult the family members or seek information about the underlying conditions of the patients.

R Jai Krishna, a public policy researcher and resident of Perambur, talks of his father who had a history of diabetes, a psychiatric condition, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and cardiac issues; he was admitted to the Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital (RGGGH) in June.

Having suffered cardiac attacks in the past, the patient had naturally lower heartbeat than a healthy adult. The history of diseases was mentioned right on the day of admission. “However, my father was still given a stimulus — to increase his heartbeat — without attention to his medical history or any consulation with family members; he could not take it,” says Jay. He feels that the number of deaths can be significantly brought down if existing co-morbidities and overall medical history of the patients are paid attention and families are consulted.

Similarly, Vinoth S* (name changed) had to run from pillar to post to find an ambulance at 2 am to admit his aunt to a private hospital. His aunt had contracted the virus during a chemotherapy session at a private hospital. Despite being recognised as a hospital that treats COVID, the patient was denied critical care.

Worse, the hospital could not even provide an ambulance for transporting the patient to another hospital. The 108 helpline remained engaged for a long time.

For over six hours, Vinoth made several calls to hospitals and officials at the corporation and an ambulance was arranged only at 8 am the next morning. By then, the patient had grown extremely critical. Even after an ambulance was arranged for, the patient was sent back by RGGGH and a private hospital.

“I received a call from one of the senior officials a few hours later and was told to head to RGGGH. By the time she was admitted to the ICU, it was 10.57 pm. However, she passed away shortly after admission,” says Vinoth.

Although there is not enough hard data to demonstrate how institutional negligence is adding to the mortality rate in the city, conversations with the families of affected persons yield disturbing stories, highlighting the challenges a patient faces in accessing admission and medical care, often leading to loss of lives in critical cases.

Together with the numbers, this creates a pressing case for overall systemic overhaul of medical governance and management of COVID-19.

(Data courtesy: Sridhar Venkataraman, a resident of Mylapore, Chennai)

Excellent data and information. Hope the Government and concerned authorities take appropriate steps for the common man.

Good article.

A candid study of the conditions prevalent in this present covid 19 scenario in Chennai. The authorities concerned must address the lacuna in these issues n evolve a system to prevent such occurrences. We can’t afford to have such institutional negligence that is causing irreversible consequences.