The revival and restoration of eris in Chennai has long captured the imagination of city authorities and residents, with these tanks often rightly lauded as an important solution to the flooding problem that has terrorised the city in the past few years.

However, a recent paper titled “Lines in the Mud”, authored by Karen Coelho of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS), points out how eri restoration efforts have become sites of social tragedy, as a result of the almost exclusive focus on removal of encroachments. They result in the brutal eviction of thousands of working class families that have struggled over decades to build a foothold in the city.

Read more: 1.2 lakh people evicted to make our cities beautiful, slum-free and smart: HLRN

The case of Korattur eri restoration

Eris are tanks that were constructed centuries ago across Southern India to trap flows of water during monsoons for irrigation purposes. Many eris that have become part of urban landscapes have either dried up, or become defunct, or have shrunk in size due to urbanisation. One such is the Korattur eri. Karen’s paper draws on the findings of a study conducted on the Korattur eri restoration efforts in 2017 and 2018.

She and her team found that there were two types of communities on two sides of the tank, with conflicting stakes in the eri. On the eastern side there were those advocating for restoration of the eri to its original boundaries. They had secure property rights, and the support of the state.

On the western side, there were informal settlements, built by low-income residents, who could not afford housing in authorised layouts. They wanted to protect their homes from demolition by the state and advocated for regularisation of their settlements.

Coelho and her team spoke to 20 residents and members of the eri restoration group on the eastern side of the eri, and participated in the restoration group’s discussions and eri-related activities. On the western side, the research team interviewed 21 residents and leaders of the anti-eviction struggle. Here too, they participated in strategy discussions and accompanied members on their visits to local officials and public consultations.

They also interviewed key officials in state agencies responsible for the Korattur eri and other water bodies in Chennai, and analysed judgements and government orders (GOs) pertaining to water bodies and restoration projects in Chennai.

Removal of encroachments

According to the paper, those leading the eri restoration efforts prioritised the notion of bringing the eri back to its ‘original boundaries’, ignoring the many changes that have altered the water body over the years. This notion of original boundaries excludes informal settlements (often termed as encroachments), that were built over the years which have altered these boundaries with time.

This was evident in quotes by leaders of the restoration campaign, as reported in the paper:

“…those who encroach must be immediately evicted, only then preservation is possible..all this happens with government support …you can buy anything with money.

If concerned people like us complain to the PWD about these encroachments, they inform and give sufficient time to the encroachers…and those people get stay orders from the court.”

The term encroachment is most commonly used to signify low-income, informal settlements along the banks of these eris and tanks, ignoring a larger history of urbanization wherein state housing complexes (such as Tamil Nadu Housing Board projects), factories, colleges and flyovers have been constructed over the city’s water bodies.

Only informal settlements targeted

In the case of the Korattur Eri Restoration efforts, the PWD, in its detailed project report mentioned how the railway line and highway across the tank contributed heavily to the fragmentation of the wetland around the eri, and that areas close to these encroachments are becoming “terrestrial patches”.

Restoration efforts have consistently resulted in widespread evictions of those living in informal settlements along the banks of these water bodies. If one were to look at restoration efforts over the years, they would see that the first order of action has been to remove these settlements and resettle those who were living in them.

Often, these settlements are framed as eyesores, reducing the beauty and property value of the area, encroaching into the ‘original boundaries’ of the water body. Their residents are seen as criminals, who have wrongfully chosen to settle on the banks, and hence they should be easily and urgently removed.

They are not looked at as stakeholders in the matter of restoration i.e. as people with rights to homes, who have a say in what happens to the water body they have lived with for decades. Restoration efforts thus seem to prioritise this notion of original boundaries at the expense of their homes, which they have worked hard to build and sustain.

Role of the judiciary

The judiciary has also come down heavily on those living on the edge of eris and water bodies, blaming these settlements for drought and flooding in the city at large. The paper cites a 2005 judgment of the Madras HC labeling these settlements as created by “unscrupulous persons” who have caused water shortage to the people of nearby areas.

In the judgment, the HC ordered all state agencies to identify and remove all of these “encroachments” along natural water sources. Using this and a number of other anti-encroachment orders made by the HC, the PWD in 2008 served thousands of demolition notices to homes on the edges of tanks in the city.

What stands out here is how settling near water bodies is seen as a choice of criminal ‘encroachers’ rather than an action driven by the lack of affordable housing options in the city.

Read More: Residents in resettlement colonies struggle with many aspects of daily life: IRCDUC study

Anti-eviction struggle on the western edge

The paper also shows perspectives of the residents of informal settlements in Korattur eri’s western side. They were engaged in a decade-long struggle to keep their homes along the banks. Their campaign centered on the claim that the eri boundaries have always been shifting, due to natural processes, settlement patterns, state policies and urbanisation, and so returning to ‘original boundaries’ is no longer as feasible as the courts and eastern residents insist.

In addition, they highlighted the selective targeting of their homes as encroachments, while there has been no such campaign to remove state built homes for more well off sections.

These residents fought in court, against the eviction notices that were served in 2008, 2016 and 2017. They advocated for the boundaries of the eri to be redrawn to recognise their long-standing occupancy on the banks and their relationship to the water body. To build their case they petitioned the DC, the local MLA and councillor, and the Human Rights Commission and organised street protests, hunger strikes and road blockages.

The paper shows how the shifting ‘natural’ waterlines of the tank over time, official records and state policies all support the claims of the western residents that the boundaries of the eri are variable and indeterminate.

Satellite images taken at different points (in 2000,2004, 2010 and 2015) highlight the seasonal and temporal nature of the boundaries.

Where are the tank boundaries, really?

The official boundaries are periodically updated after field surveys by the Revenue Department. This was last carried out in 2006–2007. The boundaries are not held sacrosanct, with a majority of encroachment in Chennai’s eris coming from government infrastructures like roads, railway lines, and residential layouts which have snipped off sections of the eri. These changes appear to have been officially recognized and reflected in the new boundaries of 2007. Thus, the official boundaries of Korattur eri have long ceased to correspond with its “original” boundaries.

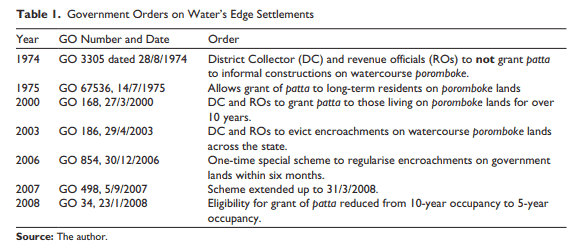

Conflicting policy signals can also be seen from the official government orders (GOs) that withheld and granted titles to those on the banks. The table below, taken from the paper, illustrates these shifts over time.

Residents of the western edge questioned why state services such as roads, water and electricity and drainage were granted to them only for them to be deemed encroachers years later.

In the case of Korattur Eri, in 2008, about 300 homes within the watershed area were demolished. In 2018, around 1000 homes were demolished.

Read More: Snapshots from Chennai’s lake restoration efforts

Rise of property-led environmentalism

According to the paper, recent approaches to tank and lake restoration are characterised by a ‘property- led environmentalism’ or ‘real estate-led environmentalism’. Environmentalism is a framework of thinking and speaking that characterises how we view the idea of ‘protecting our environment’. Property-led environmentalism prioritises property values, tourism and beautification when it advocates for protecting nature in the city, as opposed to protecting of commons.

This excludes the social dimension of urban water, in particular the habitats of people, especially of working class and property-less people, that have formed over time around the edges of water bodies.

To explain this idea of different forms of environmentalism, Karen Coelho provides a history of how the meaning and value of urban water has changed over time in Chennai. The early 20th century was characterised by constant attempts to make space for urbanisation by ‘reducing the eliminating wetness from the landscape’.

Water bodies were seen as “land in the making” to be used for housing and infrastructure. Steep population growth in the 1960s resulted in the elimination of hundreds of tanks. In the 1980s, under what is known as the Eri Schemes, many eris were filed as “defunct”, allowing for land to be supplied for housing and urbanisation projects.

It was around this time that many poor migrants who were unable to afford housing in the central parts of the city, were settled along the banks of eris with the active collusion of and by politicians, revenue officials and land agents. It was only in the late 1990s, as problems of water scarcity and flooding began to appear more frequently, that the era of restoration began to take shape, as urban water now needed to be protected.

Exclusionary nature of urban environmentalism

While lake restoration sounds quite well intentioned and is increasingly framed as an act public good, it excludes and harms many in the process. Often, propertied middle-class and upper-caste groups advocate and lead such restoration efforts. They invoke a romantic past of the water body, now lost to the ills of urbanization such as pollution, wrongful use, and, most commonly, ‘encroachments’.

Urban environmentalism advocated today tends to fixate on ideas of “pure nature” and pristine water bodies, which must be brought back to their former glory. In this dominant understanding of nature and environment, working-class settlers are criminalised as encroachers and are often framed as being responsible for flooding, drought and other environmental disasters in the city.

The paper calls for the adoption of an eco-social approach rather than a literal interpretation of “restoration”. There must be a reexamination of the meaning of restoration in an urban context and its widespread ramifications.

[With inputs from Karen Coelho]

Did the paper provide any realistic suggestions that can be taken up by the authorities?

All I read from the piece is hindsight analysis of mistakes and corruption. Middle class advocacy is being admonished. Caste is thrown into the piece for good measure.

How about pushing for affordable education and housing units in these areas by publishing some stats and real world evidence?