What if you had a say in where the public toilets in your ward are situated? Would you like to know exactly how much funds have been allocated for the creation of new civic amenities in your ward? Would you like to meet your corporator and civic authorities to put forth your grievances directly to them?

This might seem like a pipe dream for the residents of Chennai (and elsewhere in Tamil Nadu) but a coalition of citizens’ groups such as Voice of People, Satta Panchayat Iyakkam, Arappor Iyakkam, Thozhan, Makkal Paadhai and Thannatchi have come together to explore the possibilities of creating lasting avenues for citizen participation in urban local governance.

As a first step in that direction, a meeting of various civil society organisations and interested citizens was convened on May 1, to gather thoughts on the existing issues that hamper citizen participation and the means to address them. The overwhelming consensus at the meet, facilitated by Voice of People, was that the formation of ward committees was the need of the hour.

Ward committees, one for each ward in the city, along with 10 area sabhas for each ward would allow for the direct participation of citizens in local governance issues that affect them.

Status quo

The Tamil Nadu government passed amendments to the Chennai City Municipal Corporation Act, 1919 in December 2010, allowing for the provision of forming ward committees. However, the rules were never formally notified.

The city currently has 15 ward committees, one for each zone while there are 200 wards in the city. The ward committees do not serve as representative platforms for the people of Chennai and are inadequate to address issues that citizens face. With the city not having elected corporators for over two years, the citizens have effectively been frozen out of having any say in the running of the city. To remedy this, the coalition looks to follow two approaches to citizens’ participation, as seen in the state of Kerala and the city of Bengaluru.

Kerala has had a robust system in place for citizens participation in governance at the grassroots for the past 23 years, while the citizens of Bengaluru have fought hard for the institution of ward committees that are now in nascent stages, but functional.

Two speakers, one each from Kerala and Bengaluru, shared their experiences and learnings from the approaches followed in participatory governance at the meeting organised by the citizens’ coalition.

The Kerala Model

Saifudeen TS, former corporation secretary of Kochi and a faculty of the Kerala Institute of Local Administration, spoke about the process followed in Kerala. The system in Kerala is well-oiled and has been functioning over the past two decades. Steps were taken for the devolution of power to the local bodies and increased citizen participation in planning as per the 73rd and 74th amendments of the Indian constitution.

The nature of urbanisation in Kerala has been found to be different from other areas due to the rural-urban continuum, with only six cities having a population of over 10 lakhs. As such, the Kerala model is applicable to both rural and urban regions. The idea behind the systems and processes adopted in the state is that “whatever can be done at the local level must be done through devolution of powers to that level”. With this in mind, mandatory and important functions were transferred to the local bodies.

The difference between Kerala and other states in this regard is also that there has been a devolution to local bodies of 19 sector-wise functions, which in other states have been delegated to departments of the state government, para-statal bodies and special purpose vehicles.

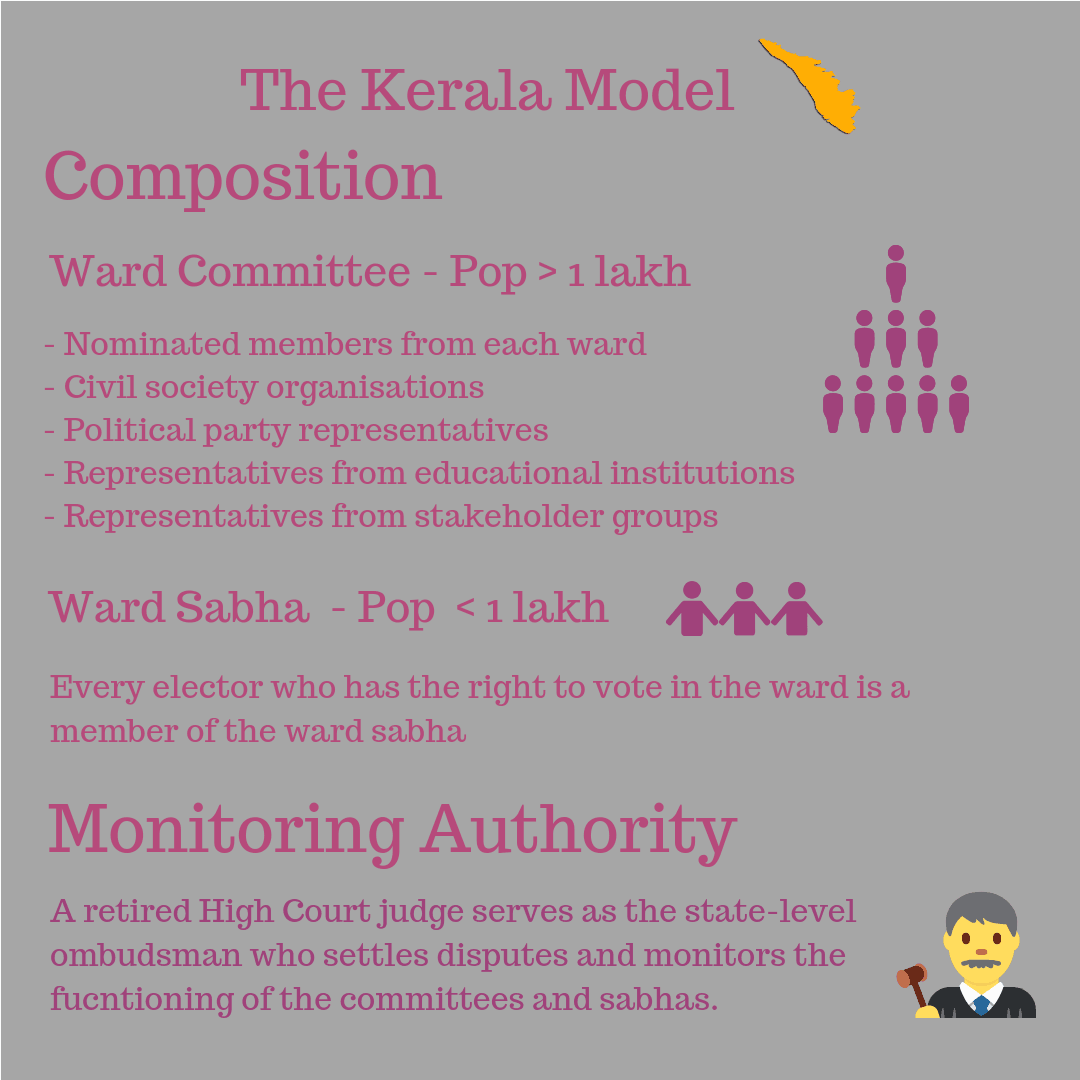

In areas where the population is greater than 1 lakh, ward committees are instituted. They include nominated members from each ward, civil society organisations, political party representatives, representatives from educational institutions and stakeholder groups. Adequate representation is ensured through mandatory reservation for women and other marginalised groups. In areas where the population is less than 1 lakh, ward sabhas are in place, where every elector in the ward is a member.

A state-level ombudsman is also present in order to monitor the functioning of the sabhas and committees and rule on any disputes or irregularities in their functioning. There are regular performance audits. There is also the presence of working groups at the level of each local body that comprises subject matter experts to aid the decision-making process. More power is vested with the citizens and elected representatives over the bureaucrats.

Saifudeen pointed out that the system is not without its pitfalls. As the Kerala model is unprecedented, there has been the need to learn through experience. He identified problem areas such as need for more training and capacity building at the official level, poor record keeping, the need to make the system more representative of marginalised groups as in practice, the need to improve service delivery and also the lack of involvement of well-to-do sections of society in the process.

The Bengaluru model

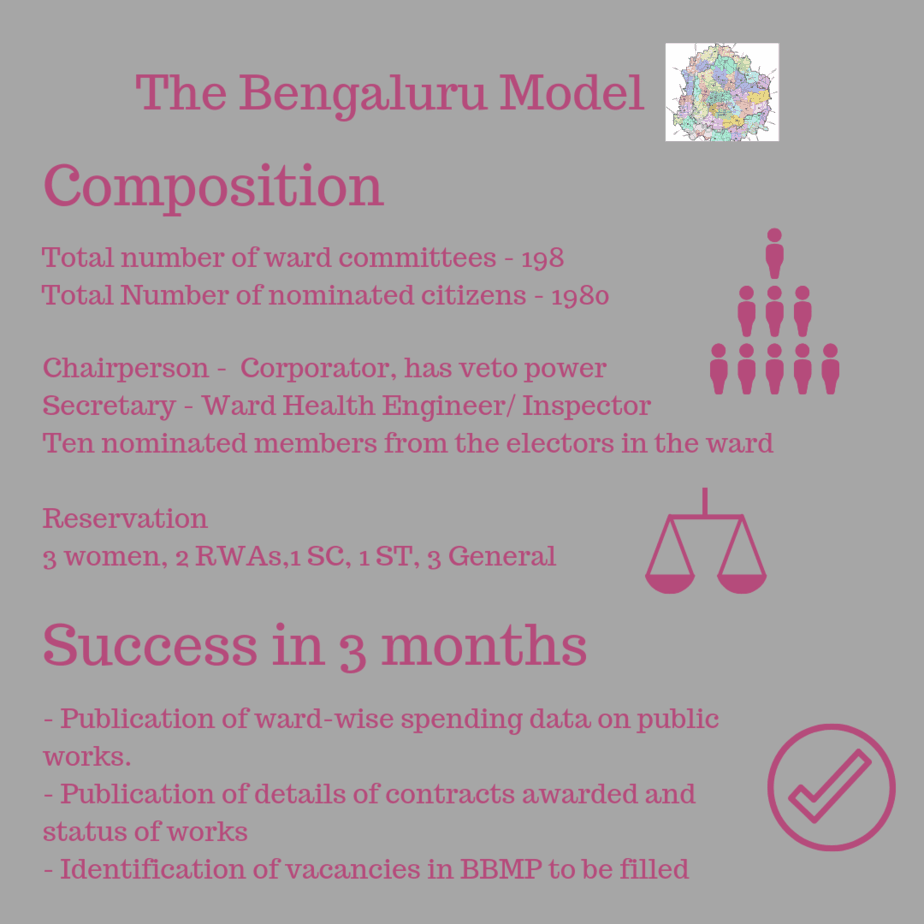

Srinivas Alavalli of Citizens of Bengaluru spoke about the efforts to create ward committees and improve citizen participation. The catalyst for the creation of ward committees in Bengaluru came with the Steel Flyover Beda movement that saw citizens come together in droves to protest a proposed steel flyover. The gathering drew the attention of the government which scrapped the project. The key actors in the movement persisted with other efforts after its success. One of the items on the agenda was the creation of ward committees in each of the 198 wards of Bengaluru.

A ruling by the Karnataka High Court on decentralisation of solid waste management, which called for oversight by ward committees, provided an opening for the pressure group to call for its formation. A meeting with the Mayor and the Commissioner of the BBMP proved positive and ward committees were instituted. The formation of the ward committees came through citizen mobilisation and protests.

With the growth of the city and its population, 198 corporators representing the interests of 1.3 crore people proved inadequate. The ward committees could serve to give additional representation. There are ten members in each ward committee along with the corporator who is chairperson with veto power, and a secretary who is the ward health engineer or inspector. The members must be registered to vote in the ward. The committee represents all sections with reservations for women, resident welfare associations and marginalised groups.

Since its inception, three meetings have been held across the wards. There has been success in terms of increased awareness among the public and the elected representatives on the need to hold such meetings. The BBMP has also published data on spending in the wards, with a break-up of funds allocated for each ward for public works, the contractors who are in-charge and the status of the works. The citizens group has established a separate database that has details of each ward committee and its members and tracks the meetings held.

The exercise is work in progress with issues of logistics, scheduling and lack of complete awareness hampering it in parts. The citizens group has identified some hiccups such as the poor command and control systems, poor record keeping and digitisation, lack of space to conduct meetings, vacancies in the BBMP and capturing of the platform by elite sections to further specific interests.

Going forward, there is hope that through collective action, such issues can be addressed to create a system that functions smoothly, as shared by Srinivas. The next step is to ensure more public participation and presence of other special purpose vehicles and para-statal bodies that are in-charge of key functions in the ward committee meetings, thus providing a channel that will further empower the people’s voices.

The institutional set-up in Kerala has been largely driven by a framework put in place through legislation while the Bengaluru model has evolved through the efforts of citizens and willing corporators. The insights from the models followed in both Kerala and Bengaluru could prove a vital starting point for efforts to be undertaken to amplify citizens voices in urban local governance in Chennai and rest of Tamil Nadu.